I’m spending part of this weekend at the Boston Music Hack Day in Cambridge, MA. Like lots of people, my ideas far outstrip my abilities and (especially!) the amount of time I have, so I thought I’d put some of them up here, in the hope that they may spark some ideas in other people.

Hacks:

Neophile: how musically alive are you? After the nth disappointment with online music licensing, and realizing that their power of the legacy record labels lies in their back catalog, I started to wonder what proportion of music that people listen to is old and how much is new. It occurred to me that you could plot a histogram of ‘number of listens’ against release date, and different people would have different distributions. For example, some people might have a peak centred around the music that came out when they were 21, whereas people who seek out new music might have a curve that’s flat or increasing with time (Paul Lamere dubbed these people ‘musically dead’ and ‘musically alive,’ respectively). The Musicbrainz database includes release years for a number of songs; with that and Last.fm scrobble data, it’s feasible to build this. I’d love to see it.

Ransom Note: I really want a ‘musical ransom note’, where you can piece together the lyrics of a song using cut-up bits of other songs. While the MusiXmatch lyrics API now provides half of that equation. I’m not sure that you can parse songs by lyrics quite yet, so this one might have to wait a bit.

Research questions:

Whose Telephone Is It? I was listening to “Teenage Kicks” (1978) by The Undertones recently, and I was struck that Feargal Sharkey sings about “the telephone” because Lady Gaga, for example, sings about “my telephone.” Somewhere in the last decade or so, telephones went from being communal property to being individual property, and this is reflected in lyrics. So I idly wondered about using the MusiXmatch lyrics API to search for instances of the word “telephone,” and to plot the frequency of the preceding article (‘the,’ ‘my,’ ‘your’) over time. This is kind of a silly example, but there is real, interesting research to be done in analysing the corpus of music lyrics using digital methodologies, for example to track social change (my friend Jo Guldi, a historian at the University of Chicago and Harvard University, does this kind of work with historical documents).

My projects:

I’ve just started re-learning how to code after many years of being strictly an experimentalist, so I have some bite-sized projects of my own that I’m working on. If you’re at the Hack Day and you’re interested in helping a Python n00b figure stuff out (like how to install matplotlib when I have Python 2.7, not 2.6) please feel free to find me.

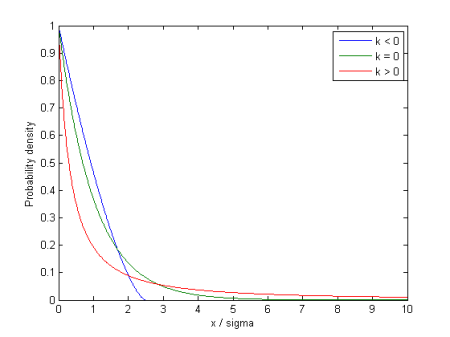

What Makes a Music Geek? The distribution of musical knowledge. Paul Lamere of The Echo Nest created Namedropper, an online ‘game with a purpose’ that let people test their musical knowledge via their familiarity with artists across a range of genres. I have a hypothesis (half in jest, I admit) that there a very few people who know an enormous amount about music and lots of people who just know a little: in other words, that the musical knowledge in a population isn’t a normal distribution about a mean, but rather a Pareto distribution (shown above). Paul was kind enough to send me his dataset from running Namedropper, and I’m planning to plot a histogram of the scores to test this hypothesis (and yes, I know that it has pretty significant methodological limitations!)

Pandora’s Redemption: A friend of mine recently tweeted, “Pandora just put John Mayer‘s “Daughters” on my 90s grrl rock station. There is no “thumbs down” button large or ironic enough.” So I’m pretty sure my first ‘real’ music hack will be to use the Echo Nest Remix APIs to try to recreate John Mayer songs out of 90s riot grrl bands like Bikini Kill and L7.

Screaming Death Metal: My technical background is in materials science, not music, and it was suggested to me that I could try to merge the two (thanks, Brian). I’ve done a lot of work with the mechanical properties of materials: putting samples of different substances (like metals, ceramics, glass and, in my case, human bone) into a machine that pulls or pushes on them and measures the amount of force required to deform and eventually break the sample, to create a stress-strain curve. The shape of the curve is characteristic of the material, and it should be possible to create an audibilization of the data that captures some of the features that are interesting to a materials scientist in a way that is discernible to the ear: in other words, creating the scream that a material makes when it’s stressed to failure.